Library Linked Data in the Cloud

OCLC's Experiments with New Models of Resource Description

Authors

Jean Godby, Ph.D.

Senior Research Scientist

Shenghui Wang, Ph.D.

Research Scientist

Jeff Mixter

Sr. Software Engineer

Chapter 3: Modeling and Discovering Creative Works

- 3.1 Library Cataloging and Linked Data

- 3.2 The FRBR Group I Conceptual Model

- 3.3 FRBR in the Web of Data

- 3.4 The OCLC Model of Works

- 3.5 Discovering Creative Works Through Data Mining

- 3.6 Chapter Summary

3.1 Library Cataloging and Linked Data

So far, the discussion has focused on the assertions about people, places, organizations, and concepts associated with the description of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Hamlet, and American Guerrilla, and many other creative works mentioned in the previous pages, but it has omitted the most important detail of all. What, exactly, is a creative work? We can presume that descriptions excerpted from WorldCat cataloging data, library catalogs, or bookseller websites such as Amazon.com are comprehensible to casual readers because they refer to objects that can be experienced in some fashion, by searching for, borrowing, buying, reading, skimming, studying, holding, or accessing via a link on a website. They are real-world objects. The view of the information consumer might also embrace the understanding that these objects were brought into being through a creative process of some sort, were manufactured into something physical or tangible, and acquired by a library, which makes them available for access. The same person probably knows that libraries have other things besides books, so a description in a library catalog can also refer to DVDs, e-books, music recordings, maps, photographs, and magazines—but is unlikely to be about electronics or kitchen gadgets. All of these statements are part of a mental model of what libraries are for, a cultural understanding that is more sophisticated than it appears, because a similar model of what Amazon.com is about would resemble the library model in some respects, but differ in others. For example, a customer’s model of Amazon would encode the knowledge that a book can be bought if it cannot be found in a library and that household items can be obtained from one source but not the other.

Chapter 1 pointed out that the description of creative works represents the leading edge of linked data modeling efforts in the library community. To make progress, three large problems must be addressed. First, creative works are ontologically complex. On the one hand, a creative work is a thought, an idea, a notion, or a search query; but it is also the physical or tangible object that is eventually obtained through the search. To model this reality, OCLC’s experiments mention all six of the key entities described in this book—People, Places, Organizations, Concepts, Works, and Objects—placing special emphasis on the last two. Another problem is that there is no ready-made or easily adaptable descriptive standard. In the library community, legacy standards are large and text-heavy, while the linked data models are still too immature to support the day-to-day activities in a library. Elsewhere on the Web, Schema.org is more established, but the model of schema:CreativeWork is richly detailed only for resources that are produced and traded through the publisher supply chain.

The final problem is that a linked data model of creative works threatens to be more disruptive to existing descriptive practice in the library community, because it falls into the divide between authority control and cataloging. As we argued in Chapter 2, a linked data representation of a library authority file can be viewed as a mostly invisible technical upgrade that establishes references to the real-world objects they describe through globally unique URIs instead of formatted text strings. But the cataloging workflow is more complex. One task is name and subject analysis, which is already taking advantage of the improved authority files produced from the linked data experiments. Another is the preparation of the item in hand for access by affixing a spine label or assigning a URL and creating a description that lists details such as the author and contributors, physical features, and multiple forms of the title. But the execution of this task exposes a tension between a quest for standardization, uniformity, or normalization (FIU 2014) and a respect for the unique attributes of the object and the librarian’s stewardship of it. For example, Martha Yee, Cataloging Supervisor, UCLA Film and Television Archive, writes:

“Can all bibliographic data be reduced to either a class or a property with a finite list of values? Another way to put this is to ask if all that catalogers do could be reduced to a set of pull-down menus. Cataloging is the art of writing discursive prose as much as it is the ability to select the correct value for a particular data element.” (Yee 2009, p. 14.)

The projects described in this chapter answer Dr. Yee’s question with a qualified ‘yes.’ Though a linked data model promises to automate many of the routine tasks in the cataloging workflow, it does not eliminate the need for discursive prose. Thus the results support the claim that linked data representations are consistent with existing norms, demonstrating a continued need for the social model of cataloging that has been practiced since the 1970s in a more robust architecture. In the linked data paradigm, the essential problem is the assignment of URIs to the resources being described—to objects in hand as well as to more abstract interpretations of creative works—and resolving the URIs to authoritative descriptions about them.

If this problem is not solved, the referents of a bibliographic description will remain lost in an ever-expanding sea of text, and redundant effort will continue to be expended in uncoordinated attempts to describe the same work or edition. But if the problem can be solved, the result will be a set of authoritative references for creative works where none existed before, an outcome that promises to promote standardization in the cataloging workflow and automate some routine tasks. This chapter and the next describe how authoritative hubs for Works and Objects are being built at OCLC. Our solution is derived from a conceptual model of Works developed in the library community and modeled in Schema.org, which we have expanded with a newly defined companion vocabulary called BiblioGraph (BGN 2014a) that extends the referential scope of Schema.org to resources of interest to the library community and the cultural heritage sector. The references are populated with data mined from WorldCat and VIAF. In Chapter 5, we will comment on the implications of these projects for future descriptive practice.

3.2 The FRBR Group I Conceptual Model

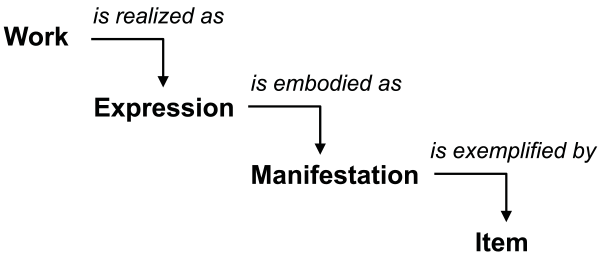

The ontology of creative works is the subject of the seminal report Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (IFLA-SG 1998), which describes a conceptual model of the contents of a library catalog developed in the 1990s. The FRBR model defines creative works as ‘the product of intellectual and artistic endeavor that are named or described in bibliographic records,’ and are connected through a chain of relationships to ‘Expressions,’ ‘Manifestations,’ and ‘Items.’ As illustrated in the widely reproduced diagram shown in Figure 3.1, a Work is realized through an Expression, which is embodied in a Manifestation and exemplified by an Item.

The best arguments for the FRBR Group I model come from the description of canonical works of world literature, which have been translated, adapted, commented upon, and republished for hundreds of years, but have their source in a single identifiable act of creative endeavor. Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a good example. As a Work, Hamlet is like the name of a law or a theorem or a hymn, whose real-world referent might be conveyed through a definition in a dictionary, library authority file, or Wikipedia page, and whose reality seems independent of any particular tangible realization. As an Expression, Hamlet is a unique text, originally written in English and translated, annotated, summarized, performed on stage, or made into a movie. As a Manifestation, the text representing a single Expression of Hamlet may be physically realized as a paperback edition published in New York in 1992 by St. Martin’s Press. And as an Item, a used copy of the Methuen edition of Hamlet can be purchased from Amazon.com or borrowed from the Capital University Library in Columbus, Ohio. The FRBR Group I model is less compelling when applied to more obscure works such as Roger Hilsman’s American Guerrilla, the World War II memoir we described in Section 1.3 of Chapter 1, because this book has a much shorter publication history and no derivatives have yet been produced. Yet a search on WorldCat.org returns a list of 10 versions that can be interpreted as different Manifestations: a hardback, a paperback, and an e-book available from Hathi Trust that was digitized in 2010 from the hardback edition published by Profile Books in 1990.

The Resource Description and Access specification (RDA 2010) develops the FRBR model into a rich set of vocabularies that define more precise relationships among the levels in the FRBR Works hierarchy and the agents involved in their production. For example, a scan of the appendices in the RDA Toolkit reveals that Works and Expressions are related to one another by relationships such as ‘Motion Picture Adaptation of,’ ‘Analysis of,’ and ‘Translation of.’ Manifestations are related through relationships such as ‘Also issued as’ and ‘Special Issue of.’ Finally, Items are connected through relationships such ‘Facsimile of’ and ‘Reproduction of,’ which are useful for describing digital objects and their physical sources, which we discuss briefly in the final section of this chapter. When these relationships are added to the rich set of roles for creators and contributors defined in the 60 years of library resource description by cataloging rules expressed in the MARC standard, it is clear that what could be said about the web of creative works and the agents that bring them into being far exceeds the descriptive capacity of Schema.org, which recognizes only a small subset of these connections.

OCLC researchers have been full partners in the development and assessment of FRBR and, to a lesser extent, RDA. For example, Hickey, O’Neill, and Toves (2002) describe an algorithm for inducing the FRBR ‘Works’ hierarchy from a corpus of MARC records such as those contributed to WorldCat, which has been applied in many research projects conducted at OCLC and elsewhere in the library community (Tillett 2003). A year later, OCLC researchers started with Smiralgia's (2001) declaration that the Work is an “essential component of the modern catalog” and highlighted the broader significance of FRBR in terms that are still relevant to our current work:

“FRBR’s core insight is that a set of entities can be identified which are key to the successful use of bibliographic records, e.g., a work, a person, or an event. These entities are related to one another in a variety of ways—e.g., a work may be created by a person, or an event may be the subject of a work. Finally, each entity is characterized by a set of attributes. A work, for example, may be defined by a title, creation date, context, etc.; a person may have a name, title, birth and/or death date, etc. This approach emphasizes not individual data elements in the bibliographic record per se, but rather the entities, relationships, and attributes the bibliographic record is intended to describe.” (Bennett, Lavoie, and O’Neill 2002)

The Bennett team argued that an entity-relationship model supports expanded options for browsing and searching a library catalog, making it possible to satisfy information requests even when they are fuzzy or vague. But given the reservations about some of the details of the FRBR Group I model—that a Work may be indistinguishable from a text (Genz 2002), that the definitions of Work and Expression overlap (O’Neill 2002; Tillett 2004), and that many resources do not require the ‘full FRBR treatment’ (IFLA 2014)—a literal formalization such as the one proposed by Hillmann et al. (2002) is unrealistic, for reasons we discuss in more detail below. Instead, the OCLC research program on FRBR supports an argument for a computationally realistic model that approximates the FRBR definitions and gathers evidence for the Group I entities by mining a large corpus of bibliographic descriptions. The research cited here hints at these conclusions, but the linked data model described in the next section of this chapter makes them more explicit.

The most visible outcome of the early research projects conducted at OCLC was the redesign of WorldCat.org as a hierarchical display. For important works such as Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, such an organization is especially urgent because users would otherwise be confronted with list of search results spanning multiple pages. But in the hierarchical display, now visible in WorldCat.org, the reader first encounters a description of the FRBR Work. From there, the reader can click on the ‘View all editions and formats’ link to view the expanded list of pointers that link to over a thousand hardback, paperback, digitized, and microform versions of the book. The resources described at these links can be interpreted as FRBR Manifestations.

In addition to the results viewable in WorldCat.org, research investigations of the FRBR Group I model have produced utilities, services, and demonstration projects that connect library resources to the wider community of information seekers. For example, the ‘xISBN Bookmarklet’ (OCLC 1998) is a Web-browser plug-in that enables a reader to discover a book of interest on a bookseller website and obtain a copy from a local library with the same or a related ISBN. The ‘Metadata Services for Publishers’ project (Godby 2010) is part of an OCLC production stream that upgrades publisher-supplied bibliographic records with subject headings, classification numbers, and authority-controlled names by assigning sparse records to a Work cluster and applying data from richer records found in the same cluster. A project with similar goals is the experimental ‘Classify’ service (Vizine-Goetz 2014a), which recommends subject headings and classification numbers for a user-submitted title by locating it in a Work cluster and applying subject metadata that has already been assigned.

Mature prototypes demonstrating cleaner, simpler displays of outputs from the FRBR algorithms are being developed for future versions of WorldCat.org. For example, in the ‘Cookbook Finder’ demo (Vizine-Goetz 2013), properties that characterize the Work independently of its physical realization, such as the title, author, summary and other descriptions of the content, are shown at the top of the page, while descriptions of the corresponding Manifestations are available in the section labeled ‘Editions’ at the bottom of the page. Links to related works, as identified by authority-controlled subject headings, are also prominently displayed. The ‘Kindred Works’ demo (Vizine-Goetz 2014b) is a companion project that recommends works of similar content identifiable from Work-level descriptions.

Underlying all of these projects are the FRBR data-mining algorithms themselves, which have undergone continuous improvement. In the 16 years since the publication of the first reports, WorldCat has grown from 48 million to over 300 million records, and the algorithms have become both simpler and more robust. We will describe the latest version of the algorithms in more detail in Section 3.5, where we show that they are an integral step in the discovery of evidence for the model of creative works published as the RDF statements accessible from WorldCat.org.

3.3 FRBR in the Web of Data

OCLC’s research supports the conclusion that at least two levels must be recognized in the FRBR Group I hierarchy. A creative work is an abstract idea that prompts the user’s information request, which corresponds roughly to a FRBR Work. A creative work is also the physical or tangible object that ultimately satisfies the request, which can be modeled as a FRBR Manifestation or Item.

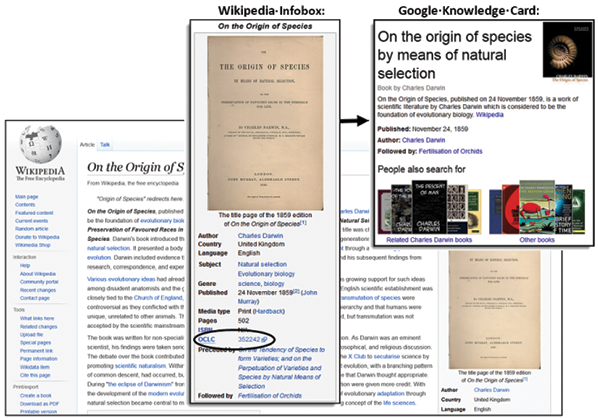

As we have seen, OCLC’s implementation of this distinction is designed to facilitate searching and simplify the display of WorldCat.org and individual library catalogs. But it is now becoming visible in the Web beyond the library community. For example, Figure 3.2 shows the English-language Wikipedia page for On the Origin of Species. The Infobox on the right side of the page is reproduced in the magnified inset in the center of the image. It is populated with authoritative structured data, including the publication date, a digital image of the title page of the first edition, and a link to the same work in described WorldCat.org. A Google search for On the Origin of Species produces a front page with the Knowledge Card shown on the right, which cites Wikipedia as a source and contains some of the same structured data.

These examples demonstrate the theoretical possibility that library resource descriptions could be exposed to the wider Web, where a reader could search for a creative work on Google or Wikipedia and follow a link to a nearby library to obtain an object with the desired physical characteristics. But today this vision is only partly realized. The link to WorldCat.org resolves to a page that is still too difficult to navigate. And the Google Knowledge Card contains a link only to the HarperCollins edition published in 2012, but not to any of the other editions and formats described in WorldCat—including the original edition, which is highlighted on the Wikipedia page. Such gaps and inconsistencies imply a need for a more abstract conception of the Work such as the one we have discussed, which libraries and aggregators of library metadata such as OCLC are in the best position to define. When it matures, a model of the creative work that includes this level of description would rectify a larger problem than any of the shortcomings pointed out here. Neither Wikipedia Infoboxes nor Google Knowledge Cards even exist for the vast majority of resources held by libraries because they are not exposed as structured data on the Web at all.

To address these problems, we are packaging the library community’s understanding of creative works ‘in the form that the Web wants,’ to use a phrase popularized by our OCLC colleague Richard Wallis (Wallis 2014b). In operational terms, this means that the output of OCLC’s FRBR data-mining algorithms are being integrated into the model of creative works derived from Schema.org that underlies the linked data markup published on catalog records accessible from WorldCat.org. An account of how this is done occupies the rest of this chapter.

3.4 The OCLC Model of Works

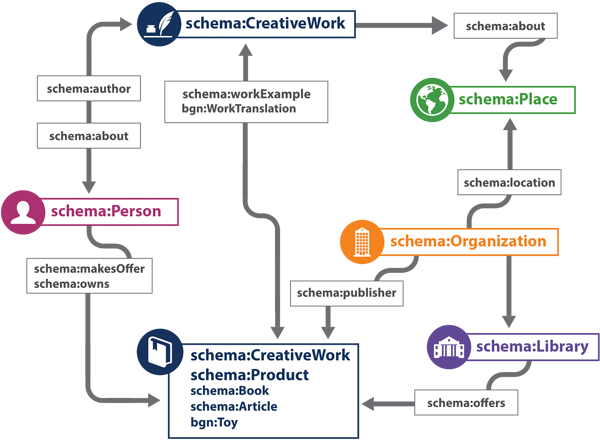

OCLC’s model of creative works is grounded in the conviction that the fundamental interactions between information seekers and creative works that motivated the FRBR Group I conceptual model—finding, identifying, selecting, and obtaining—are as relevant on the wider Web as they are in a single library catalog and must be represented in a formal model. But as we have seen, it is difficult to design a model of Works, Expressions, Manifestations and Items that is applicable across the broad spectrum of resource types managed by libraries and to discover evidence for these distinctions in legacy bibliographic descriptions. The problem arises because the four concepts defined in the Group I hierarchy are typically modeled as classes, making it necessary to define rules that can distinguish them. We are exploring the alternative hypothesis that much of the FRBR Group I model is expressible through properties defined on just two classes—namely, schema:CreativeWork and schema:Product, which can be used to define a set of connections among Works, People, Objects, Organizations, Places, and Concepts involved in the creation, production, and management of intellectual capital by libraries and other communities with similar interests. The result is a lightweight, flexible model that can be discovered by mining WorldCat or other collections of bibliographic records.

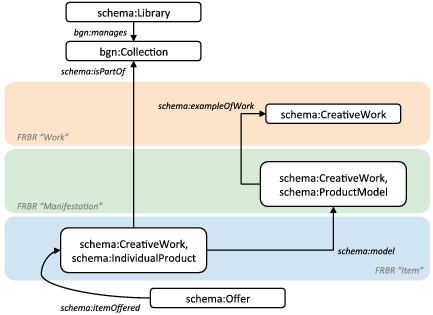

Figure 3.3 shows a high-level web of relationships for all six of the key entities we have discussed throughout this book, this time in more technical detail. In fact, the figure is simply a variant of Figure 1.1, the very first figure displayed in Chapter 1. At the center is the distinction between the Work as content and the Work as a product or object, enhanced with a set of relationships that can be derived from research on FRBR and RDA. Thus, a Work can be a translation of another Work, such as a German translation of Beowulf ; a Work can originate from the same act of creative endeavor as another Work, as when Hamlet is realized either as a play or as a book for young adults; or a Work can be viewed as a Product, which is borrowed from a library or lent to a patron. A Work can also be ‘about’ a Person, Place, or Organization. The other key entities also have relationships with creative works, such as the Person acting as an author who creates content; the Organization acting as a publisher that transforms the content into a product; or a library, a subclass of Organization, which acquires, lends, and licenses the product to patrons. Though the model is a variant of a hub-and-spoke design with two types of creative works in the center, the key entities may also have relationships with one another, such as the ‘location’ relationship between an Organization and a Place that could be defined in a lower level of modeling detail.

Schema.org provides a rich foundation for the definition of creative works that can support the needs of libraries, but the labels shown in Figure 3.3 identify an additional source of vocabulary. As expected, terms defined in the ‘schema:’ namespace represent concepts imported from Schema.org for naming the most important classes and subclasses and many properties. In addition, terms defined in the ‘bgn:’ namespace represent concepts imported from BiblioGraph.net, an experimental extension vocabulary for Schema.org developed by OCLC researchers for the description of library resources in a format suitable for use by the information-seeking public on the wider Web (BGN 2014a). BiblioGraph.net is a more sophisticated implementation of the experimental ‘library’ vocabulary published in the first- generation RDF markup on WorldCat.org and has been heavily influenced by the principles and recommendations of the W3C-sponsored Schema Bib Extend Community Group (Schema Bib Extend 2014d), about which we have more to say below. In building out the model, our goal is to define additional subclasses of schema:CreativeWork and properties that define a more detailed view of library resources, from which a high-level model of typical library transactions such as acquiring, lending, and preserving can eventually be defined. Taken together, these concepts and their interrelationships comprise OCLC’s model of creative works—or simply ‘Works,’ to use the term we have mentioned throughout this book.

3.4.1 Extending Schema.org

In Schema.org, CreativeWork is a subclass of schema:Thing, for which properties such as ‘name’ and ‘description’ have been defined. Properties for schema:CreativeWork include those typically mentioned in the descriptions of FRBR Works and Manifestations, such as schema:publisher, schema:datePublished, schema:typicalAgeRange, schema:inLanguage, schema:about, and so on. Subclasses of CreativeWork defined by Schema.org include schema:Book, which supplies a set of even more specific properties such as schema:numberOfPages and schema:illustrator. Thus the class and property chains in the Schema.org ontology are both hierarchically structured and flexible, which we exploit in the design of the OCLC model of Works. Refinements to Schema.org can be made with relative ease because of relaxed requirements for type assignments. Though the hierarchy labeled with the terms ‘Thing - CreativeWork - Book’ defines a class and property chain, all of the properties are optional and may even move up the chain—forming, in effect, a loosely typed universe of descriptors from which a set of more or less detailed statements about a resource can be constructed.

The draft specification for the enhanced vocabulary available from BiblioGraph.net has the same organization as Schema.org because it is derived from the same open source software platform. Built from Python scripts and cascading style sheets, the software creates displayable pages from a source file containing the complete vocabulary specification for Schema.org represented in the RDFa Lite format (Schema 2012). The OCLC project team has added a corresponding RDFa Lite file containing the BiblioGraph extensions (BGN 2014b), modified the stylesheets to produce some lightweight BiblioGraph branding, and enhanced the software to accept multiple namespaces and type inheritances. To keep the two vocabularies synchronized, the process for building BiblioGraph.net uses the latest copy of the Schema.org and merges it with the BiblioGraph extensions. Duplicate terms are managed in these specification files, which identifies the presence of the ‘supersedes’ and ‘supersededBy’ relationships between terms.

For example, the class bgn:Agent, defined as a parent of schema:Person and schema:Organization, contains two new properties, bgn:publishedBy and bgn:translator. This class permits accurate statements about creative works when the class membership of the creator, translator, or publisher is unspecified or irrelevant. Most BiblioGraph terms define new properties or subclasses of schema:CreativeWork, such as bgn:Newspaper, bgn:Thesis, bgn:Chapter, or bgn:MusicScore. Since most extensions are straighforward, it is easy to imagine how they would be positioned in the Schema.org ontology. But other subclasses are ontologically more complex. For example, bgn:Toy takes advantage of multiple type inheritance, an under-documented feature of Schema.org that is a consequence of its compatibility with RDF-Schema (Brickley 2010; Ronallo 2013). With two parents, a toy can be interpreted from two points of view. As a subclass of schema:CreativeWork, it can be understood as a genre or resource type analogous to schema:Book or schema:Movie. But described as a schema:Product, a toy can also be understood as a real-world object that can be bought, sold, lent, borrowed, and played with.

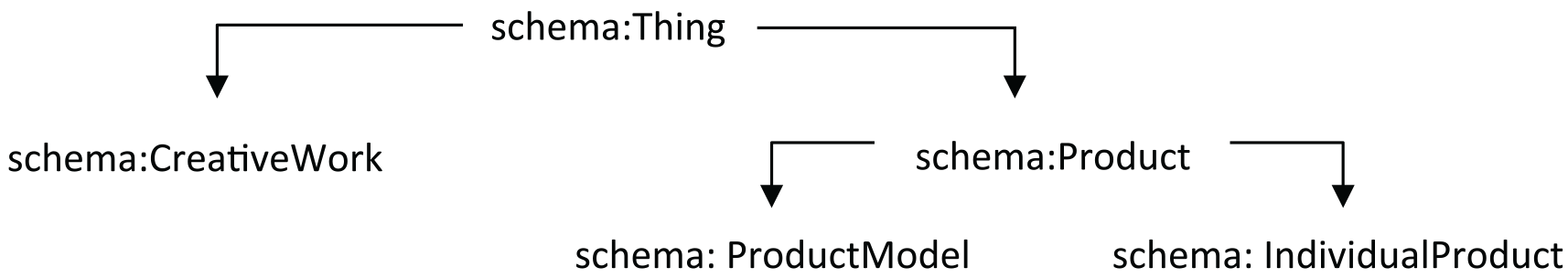

Multiple inheritance from the schema:CreativeWork and schema:Product class hierarchies is instrumental in drawing the distinction between the Work as Content and the Work as Object that is fundamental to the OCLC model of Works. As shown in Figure 3.4, subclasses of schema:Product introduce concepts that make it possible to refer to creative works realized as unique objects or as identical members of a set. Thus schema:IndividualProduct is “a single, identifiable product instance (e.g., a laptop with a particular serial number)” (Schema.org 2014b) and schema:ProductModel is a “model or vendor specification for a product” (Schema.org 2014a), while schema:SomeProducts is a subset of identical objects that are not individually identifiable.

With properties available both from schema:CreativeWork and schema:Product, different kinds of assertions can be expressed about the ‘Toy’ class defined in BiblioGraph.net, which might be associated with lifecycle events. For example, a set of statements that make the dual rdf:type assignments of schema:CreativeWork and schema:IndividualProduct can describe a creator's unique object, such as a prototype electronic game that teaches children to write by tracing lights on a small console with a stylus. Once the game is manufactured and made available for sale from Amazon.com, it is assigned the product identifier ‘B001W2WKS0,’ which uniquely identifies the version of LeapFrog Scribble and Write produced by LeapFrog in 2014. Since a product identifier can be interpreted as a model number, the set of objects with the same code can be described as a schema:ProductModel. When this version of the game is purchased, a single exemplar is sent to the buyer–which, like the original prototype, is described as schema:IndividualProduct and schema:CreativeWork. But now it is a member of a set of identical manufactured objects, a reality that be expressed through a statement containg the property schema:model, which associates the object with a description of the corresponding schema:ProductModel class. When the physical realization is not known or does not matter, however, as in the assignment of intellectual property rights, no value from the Schema:Product class needs to be assigned at all and the single type assignment schema:CreativeWork is sufficient.

3.4.2 Modeling FRBR Concepts in Schema.org and BiblioGraph

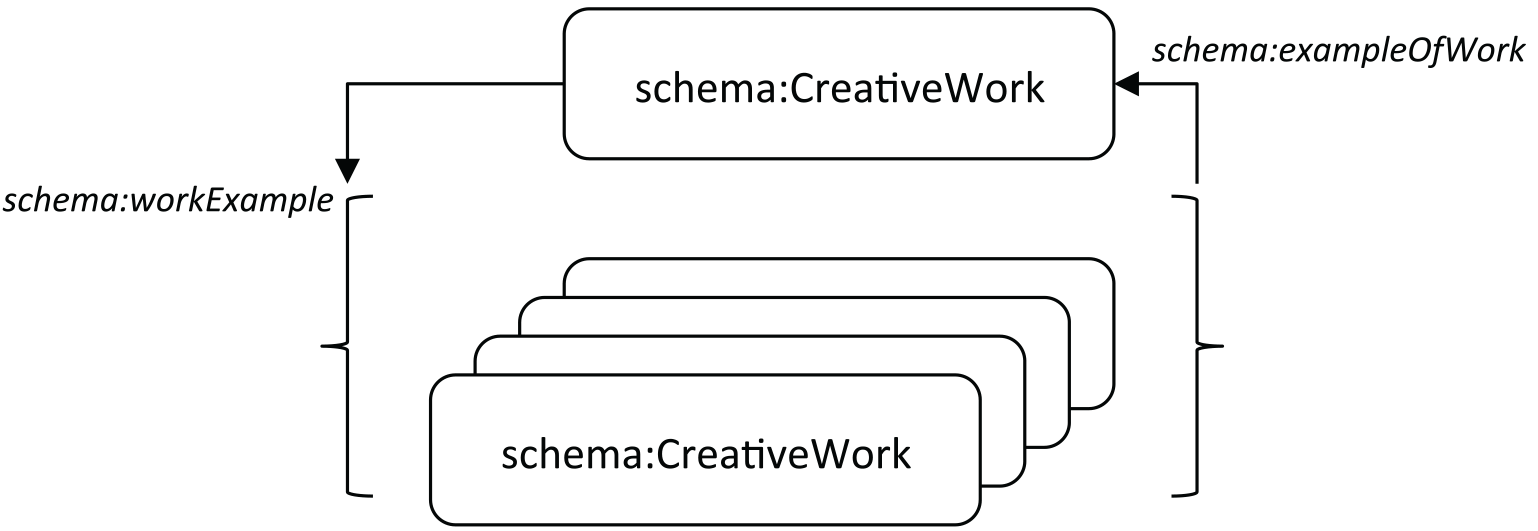

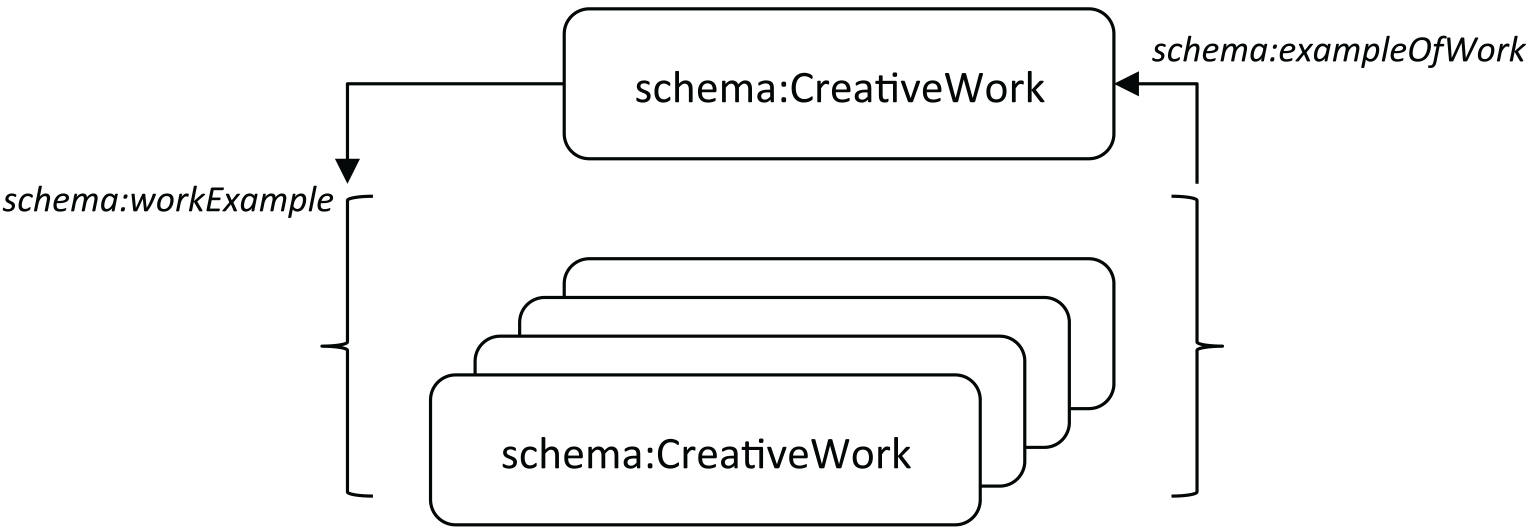

The flexible design features of Schema.org and the BiblioGraph extension vocabulary are used to build out a model of Works that recognizes the most important distinctions captured in the FRBR Group I model. At the highest level, the model establishes a one-to-many relationship between an abstract creative work and a set of creative-work ‘objects’ and expresses it through reciprocal links accessible from WorldCat.org and WorldCat Works (oclc2014˙workdev ), an RDF dataset that defines clusters of library resources described in WorldCat catalog data that have the same content-oriented properties. Though designed for machine consumption, a WorldCat Work description can be viewed through the human-readable ‘WorldCat Linked Data Explorer’ interface when a known URI is supplied. Some examples are discussed below. As shown schematically in Figure 3.5, this model asserts an abstract, or null, relationship between resources typed as schema:CreativeWork, defined using the generic properties schema:workExample and schema:exampleOfWork. These terms were proposed as extensions by the Schema Bib Extend Community Group in early 2014 and have recently been been adopted by Schema.org (Wallis 2014a).

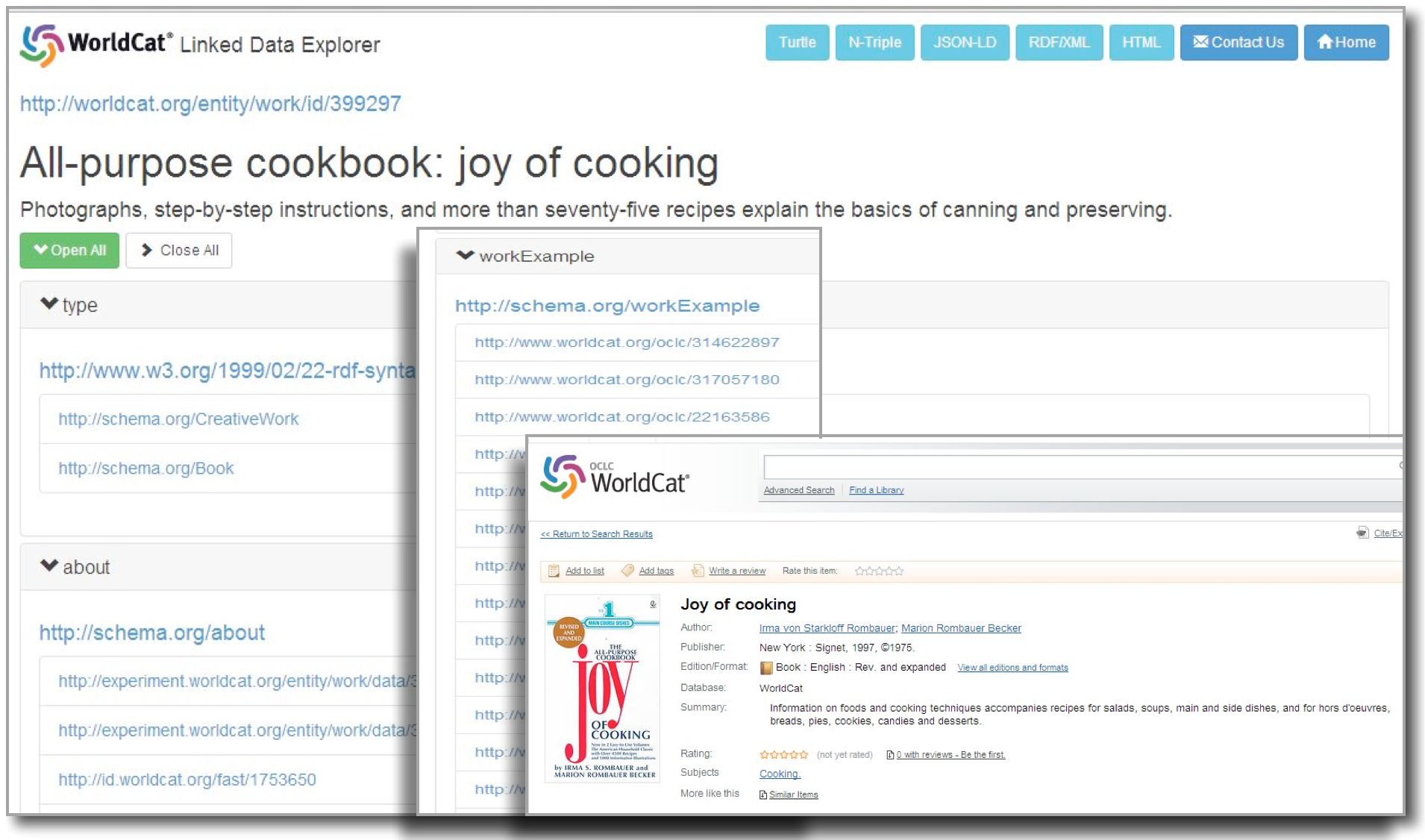

The same relationships are shown in more concrete detail through evidence discoverable from a search on WorldCat.org for the edition of Joy of Cooking published by Scribner in 1997. Figure 3.6 shows the two types of resources. In the foreground, in the bottom right corner of the image, is a page accessible from a WorldCat search describing a human-readable summary of a MARC record. It is recast in this model as a ‘Work example,’ defined in Schema.org as an “...Example/instance/realization/derivation of the concept of this creative work” (Schema.org 2014c). In the background is the corresponding ‘Work’ page defined in WorldCat Works, which contains RDF statements describing the title, author, subject headings, summaries, and other content-oriented metadata applicable to all versions of Joy of Cooking when viewed from a higher level of abstraction that omits the details of physical realization. The image in the center is an excerpt from the list of schema:workExample statements available from the WorldCat Works page, which identifies the complete set of URIs for the corresponding resources described in WorldCat to which the ‘Work’ concept applies.

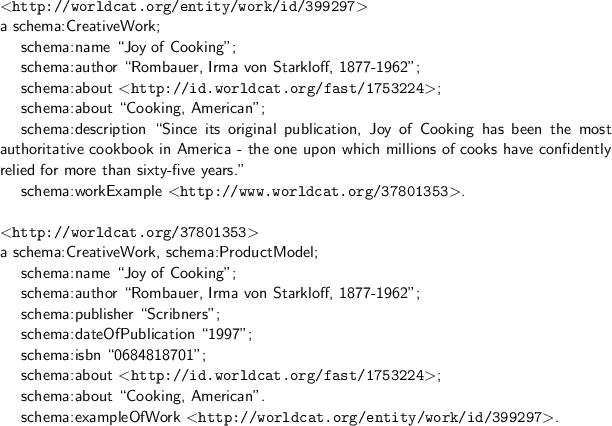

Excerpts from the corresponding RDF/Turtle instance data are shown in Figure 3.7. In the first block, the WorldCat ‘Work’ is typed as schema:CreativeWork and contains properties defined by Schema.org for the content-oriented metadata. This block is linked by a set of schema:workExample statements to a collection of published editions, one of which is referenced in the second group of statements. These statements have been selected from the description published in the ‘Linked Data’ section of the WorldCat.org page for the 1997 Scribners edition shown in Figure 3.6. The statements in this block also refer to an object typed as schema:CreativeWork. But because this description contains details that identify the referent as a particular class of products manufactured in the publisher supply chain, such as a publisher, publication date, page count, and ISBN, a data-mining process applied to WorldCat can discover evidence that justifies an additional type assignment of schema:ProductModel. Because of the difference in RDF type assignments, a machine process can distinguish between the two kinds of creative work.

Thus the relationship between a Work and a ‘Work example’ is akin to the relationship between a FRBR Work and a Manifestation. If the object is a printed book or a manufactured CD that is a member of a set of identical exemplars, the description will typically contain product identifiers such as ISBNs. If it is an e-journal or e-book, the description will contain properties that identify ISSNs or DOIs. Though many characteristics of creative works produced by commercial publishers can already be described by properties defined in Schema.org, extensions defined in the BiblioGraph extension vocabulary will be required to describe those of special interest to libraries, such as unique manuscripts, archives, theses or digitized collections. But from the perspective of the larger Schema.org ontology, all physical or tangible objects justify a type assignment from the schema:Product, which makes Works as Objects ontologically distinct from Works as Content without triggering the need to recognize a separate class such as ‘frbr:Manifestation’ in the model.

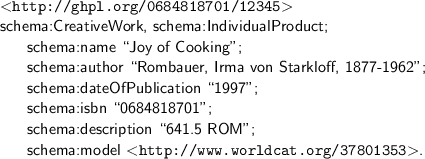

This model is easily extended to include a FRBR-inspired Item. Figure 3.8 shows a hypothetical set of RDF statements describing a copy of the Scribners edition of Joy of Cooking available from Grandview Heights Public Library. Like the companion description of the Manifestation shown in Figure 3.7, the RDF representation identifies an author, title, and publication details. But because this description refers to a copy, it contains additional properties that trigger the assignment of schema:IndividualProduct, such as a unique shelf location, captured here in the schema:description field; or, more plausibly, a barcode or spine label. The relationship between the Manifestation and Item can be captured by the property schema:model, already defined for schema:Product, which can be fashioned into a statement about set membership. This copy of Joy of Cooking is identified as an exemplar of the product whose description is accessible from WorldCat.org at the URI ending in 37801353.

The hypothetical copy of Joy of Cooking available from Grandview Heights Public Library presents an opportunity to point out two design features of OCLC model of Works: a more flexible model of FRBR Group I concepts, and a richer and ontologically more natural model of holdings than the existing record-oriented descriptive practice. In current systems, a library holding is a noun, or a ‘Thing,’ perhaps because a status bit is set in an aggregated database of bibliographic records such as WorldCat whenever a library claims ownership of a particular title. But outside the context of a record-oriented architecture, a library holding is expressed more intuitively as a relationship involving a library, a creative work, and terms of access. A high-level view of a model that is consistent with the OCLC model of Works is shown in Figure 3.9.

The multicolored ribbons in the diagram illustrate the FRBR-like distinctions between Work, Manifestation, and Item implicit in the RDF statements shown in Figures 3.7 and 3.8. A set of statements about a volume with a complex publication history such as Joy of Cooking makes reference to these three concepts, but the diagram implies that links to Work and Manifestation descriptions may not be necessary for some kinds of resources. For example, if the Item in the collection is a unique object, such as a handwritten journal or a collection of photographs assembled by a local historical society, the resource could be described as a schema:IndividualProduct, which would not require a schema:model link to other concepts defined in the FRBR Group I hierarchy.

To account for library holdings, the model is extended in two ways. First, the model must describe the larger context of a library with at least one collection. A library can be identified with schema:Library, but a suitable concept of ‘Collection’ may require a refinement of the existing Schema.org draft or a redefinition as a term of art in the BiblioGraph namespace. A hypothetical property such as bgn:manage could associate the library with its collection; and once connected, the schema:isPartOf property can identify the held item as a member of the collection. But the most novel part of this analysis stems from the description of the library’s terms of accessibility in the schema:Offer class. For example, a rich set of schema:Offer properties such as schema:businessFunction, schema:itemAvailability, schema:availabilityStarts and schema:availabilityEnds can be used to craft a detailed description specifying that a book can be lent for a two-week period to library cardholders, who are levied a fine if it is returned after the due date, and so on. The schema:Offer class is linked to the schema:Product hierarchy by the schema:itemOffered property, creating a point of entry into the GoodRelations ontology (Hepp 2014), which was recently absorbed into Schema.org.

Though designed for commerce, the properties and classes defined in GoodRelations make it possible to publish the business logic of an important library transaction in a format that is completely machine-processable and capable of interpretation by general-purpose search engines. Current library catalogs derive their implementations from the MARC 21 Format for Holdings standard (LC 2000) to define a locally maintained record consisting primarily of human-readable text that lists the title, author, and product and item identifiers, and describes the unique physical location of the item on a particular shelf in a building. Such records are difficult to maintain and are accessible only from the software applications maintained by the library and are not visible on the broader Web. But with a dual type assignment of schema:CreativeWork and a value from the schema:Product vocabulary, a library resource can be understood as an object that participates in transactions involving people and institutions.

Most of the details of the model of library holdings depicted here were developed in the Schema Bib Extend Community Group (Schema Bib Extend 2014b), which took on the task with the intention of making recommendations to Schema.org for class and property extensions. But in the end, no significant changes were required, except a recommendation to broaden the meaning of schema:businessFunction and schema:seller to include the possibility that libraries have a ‘vend’ relationship with the resources that they manage and make available to patrons.

Modeling FRBR Expressions

The discussion above has shown that the OCLC model of Works accounts for the differences between Work as Content and Work as Object by making reference to the properties listed in a resource description, many of which have already been defined in Schema.org. Though some differences in detail are ontologically significant, resources typed as schema:CreativeWork have been linked with one another only by the semantically non-committal properties schema:workExample and schema:exampleOfWork.

What is missing in the model is an account of Content-to-Content relationships, which are interpreted in the FRBR Group I model as relationships between Works and Expressions. As described in the FRBR and RDA scholarship, Expressions of the same Work produce different texts or performances—as a translation, a revision, an adaptation, a new edition, a new arrangement, or other changes that largely preserve the creative intent of the original endeavor. But as we noted in the previous section, even the earliest research on FRBR revealed fuzzy boundaries between FRBR Works and Expressions. Recent studies have renewed the argument that an ontologically distinct FRBR Expression is valuable for use cases that identify commonalities among some creative works (Zumer, O’Neill, and Mixter 2015), but the complexity introduced by an additional concept must be weighed against the problem of requiring distinctions that may be difficult to discover algorithmically.

In the context of the OCLC model of Works, this uncertainty implies that the evidence discoverable in bibliographic descriptions is insufficient to justify the definition of a class in the model such as ‘frbr:Expression.’ Instead, the Content-to-Content relationships that underlie the reality of FRBR-like Expressions are expressed as properties of schema:CreativeWork. Accumulating evidence discovered by a data mining algorithm operating on bibliographic metadata can trigger a more specific property than schema:workExample, such as ‘is translation of,’ ‘is adaptation of,’ or any number of other relationships that have already been proposed. We illustrate this feature of the model using OCLC’s Multilingual WorldCat project.

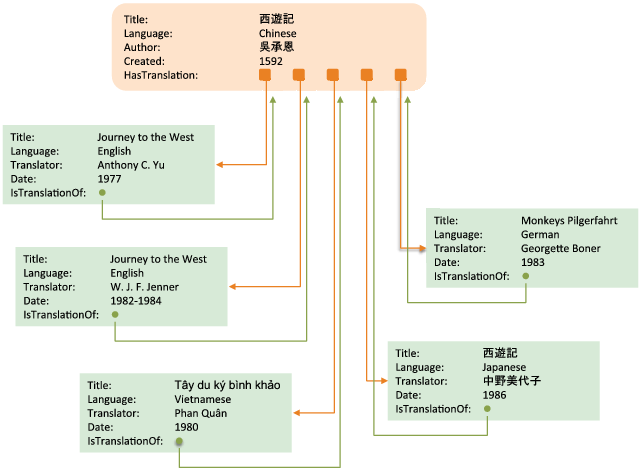

Nearly half of the bibliographic descriptions in WorldCat are written in languages other than English, many representing translations of humanity’s most important cultural and intellectual heritage (Smith-Yoshimura 2014b; Gatenby 2013). The records in this subset of WorldCat consist primarily of textual descriptions that are not machine-understandable. But at its core, an improved model of translations must recognize three properties: the language of the target text, the language of the source text, and the ‘translation’ relationship between the source and the target. A more complete description would also include the name of the translator and properties that encode the text, such as character sets, character encodings, and transliteration schemes. The schematic in Figure 3.10 suggests that all characteristics except the ‘translation’ relationship can be defined as properties on schema:CreativeWork. Some, such as schema:inLanguage, are already part of the standard; others, such as bgn:translator, are being defined in the BiblioGraph.net extension vocabulary. But since translations are Content-to-Content relationships among resources typed as schema:CreativeWork, they are linked by the more specific properties bgn:workTranslation and bgn:translationOfWork instead of the generic schema:workExample and schema:exampleOfWork.

Figure 3.11 illustrates a network of relationships that can be induced from data available from WorldCat for a Chinese-language Work translated into English as Journey to the West. Details about the source description are shown in the orange box and the corresponding details for English, Vietnamese, German, and Japanese translations are shown in green boxes. The color coding is consistent with the with the model of holdings shown in Figure 3.9 and implies a Work-Manifestation relationship between the 16th-century Chinese novel and its derivatives. This example has been simplified for ease of exposition, but WorldCat catalog records contain an abundance of detail that would trigger a type assignment from the schema:Product class on the derivatives—such as publication dates, publishers, and page counts—which is absent in the description of the source. In effect, the figure implies that Content-to-Content relationships such as ’translation of Work’ and the properties important for drawing distinctions in the FRBR Group I hierarchy in the OCLC model of Works are orthogonal and can freely co-occur.

As in the model of library holdings, the research on multilingual bibliographic descriptions underscores an important difference between the OCLC model of Works and previous implementations of the FRBR Group I conceptual model: the hierarchical relationship among Work, Expression, Manifestation, and Item is not required or even presupposed. It is simply one possible configuration among many.

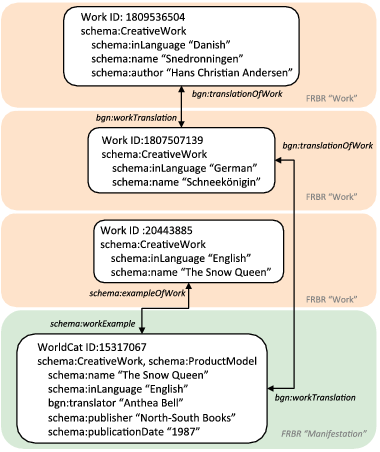

For example, Figure 3.12 shows relationships among translations of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale Snedronnigen in slightly more detail. At the bottom of the figure is a MARC description for an English translation of Snow Queen, which contains publication details that generate a schema:ProductModel type assignment and can be interpreted as a Manifestation. The MARC description reveals that the source is a German translation titled Schneekönigin, not the Danish original. According to a note in the MARC description, the German translation was first published in Switzerland, but it does not contain enough evidence to identify a particular edition. Since WorldCat contains many German translations of Snedronnigen, a Work cluster can be inferred. A Work cluster of English translations can also be inferred, which contains the version of Snow Queen translated by Anthea Bell as a member, or a ‘Work example.’ But inside the cluster of English translations, the translation sources may differ; what is known for certain is only that the source for the Bell translation is an unspecified member of the German translation Work cluster. This relationship is captured with bgn:workTranslation and bgn:translationOfWork properties between the English Manifestation and the German Work shown in the diagram.

In effect, the Multilingual WorldCat project provides much-needed empirical input to a model of translations. Instead of encoding a theoretical pronouncement that a translation is a relationship between Works, or between a Work and an Expression, a model derived from data can describe a more nuanced reality. Sometimes the translation source is a chain of translations that lead only indirectly to the original work, as Figure 3.12 shows. Sometimes the translation is derived from a particular Manifestation and has sibling relationships to other translations, but often the textual source of the translation is not specified at all.

Summary: FRBR in the OCLC Model of Works

As we first pointed out in the discussion of Figure 3.1, previous formalizations had translated the FRBR Group I model, and the RDA elaborations of it, into a class hierarchy with exactly four levels, connected by properties with rigidly specified domains and ranges. For example, the RDA Relationship ontologies define ‘Translation of’ as a relationship between Expressions, while ‘Contained in’ is a relationship between Manifestations (RDA 2010). But in the OCLC model of Works, the hierarchy of the FRBR data model has been flattened while retaining the essential meaning of the concept definitions. This result is accomplished by representing three of the categories in the FRBR Group I Model as instances of schema:CreativeWork with different properties, assigning a value from the schema:Product ontology if certain details are present, and redefining the relationships among FRBR Expressions as Work-to-Work relationships. Thus the hierarchical model of FRBR and RDA has been replaced with a ‘trigger’ model, which means that most schema:CreativeWork properties are not ontologically distinctive; only those that imply physicality or set membership are. The most important consequence of this design is that the concepts originally defined in the FRBR Group I hierarchy can expand, repeat, or collapse depending on the quality of the data and the type of resource being described.

3.4.3 A Note About URI Design

In this overview of the OCLC model of Works, one remaining technical detail needs to be discussed: the syntax and semantics of the URIs. As we first pointed out in Section 1.3 of Chapter 1, all URIs published in OCLC’s RDF datasets follow the W3C’s Cool URIs convention (Sauermann and Cyganiac 2007) and resolve via the HTTP 303 direct protocol to a Generic Document with authoritative information about the resource, whose format is delivered to the users device through content negotiation. The pages available from WorldCat Works can be understood as Generic Documents for Works, as can some pages available from VIAF. The end of Chapter 2 pointed out that VIAF contains descriptions of more than two million uniform titles, an artifact of the traditional library authority file that is still useful because it contains highly reliable, controlled strings representing the original title of a Work and its translated forms recognized by the library community. Joy of Cooking is among the many Works that do not have a uniform title description, but a VIAF description accessible at http://viaf.org/viaf/185090227 is available for the Chinese literary classic translated as Journey to the West, which is depicted in Figure 3.11. The Cool URIs convention permits RDF statements asserting that the VIAF URI and the URI associated with the corresponding WorldCat Works page refer to the same real-world object.

The syntax of the URIs is still in flux because several experiments are being conducted in parallel and must be compatible with legacy data stores and software processes. As the instance data excerpted in Figure 3.8 shows, the special status of a WorldCat Works URI as an identifier for a Work entity can be parsed from the token sequence http://worldcat.org/entity/work/id. But it is associated by the schema:exampleOfWork property with legacy WorldCat URLs, such as http://www.worldcat.org/37801353, from which no such interpretation can be inferred. Right now, the referent of the WorldCat URL is a bibliographic record, but it is expected to evolve into a schema:CreativeWork realized as a FRBR Manifestation when the model of creative works described in WorldCat is more mature. The URI could be expected to have the form worldcat.org/entity/manifestation/id, matching the pattern of the WorldCat Works URI, but such a design is not required for fully RDF-aware software processes that can read the description directly to identify the referent as a schema:CreativeWork. Once RDF datasets and software environments achieve critical mass, we may opt to redesign the URIs as semantically opaque strings analogous to those now available from VIAF.

3.4.4 BiblioGraph: A Curated Vocabulary for Schema.org

OCLC’s model of Works is derived from Schema.org and supplemented with vocabulary defined in BiblioGraph, which uses linked data principles and practices to describe entities and relationships that matter to those interested in the domain of bibliographic description. To echo the language used by R.V. Guha and other Semantic Web experts, this design responds to those who have both simple and complex things to say about resources that need to be more easily discoverable on the Web. Thus Schema.org was designed as an easy-to-use vocabulary for webmasters, which purposely omits the specialized vocabularies of individual professions or communities of practice. But linked data models in all domains are still immature and evolving rapidly, and even general-purpose vocabularies such as Schema.org still have genuine gaps.

As we said above, BiblioGraph is a proving ground for supplementing Schema.org with vocabulary required for the development of models in the domain of library resource management. BiblioGraph addresses two long-term goals. The first is to identify simple, commonsense terms such as ‘translation,’ which are intuitively comprehensible and potentially useful to the information-seeking public. The second goal is to identify terms such as ‘Agent’ that permit true but complex statements about our domain that may be of interest only to professional managers of bibliographic description. The distinction may be subtle, but it is clearly drawn in the model. The first term is a candidate for formal inclusion in the Schema.org vocabulary and would be represented as schema:translation. The second term retains its definition in the BiblioGraph namespace as bgn:Agent, though it can be positioned in the formal structure of the Schema.org vocabulary. A team of editors and advisers will conduct the analysis required to accomplish these goals as they continue to develop the BiblioGraph vocabulary.

In the process of defining the domain of bibliographic description, the BiblioGraph editors have also discovered accidental gaps in Schema.org. For example, ‘Toy’ is clearly not a technical term unique to librarianship, though a MARC record accessible from WorldCat.org reveals that the electronic game Twist & Shout Multiplication, mentioned earlier, is held by a school library in Noblesville, Indiana. Thus it seems likely that ‘Toy’ will by added to Schema.org through some pathway not involving BiblioGraph. If this happens, BiblioGraph will be modified to remove the redundant term, as it was when the bgn:VideoGame class was recently deprecated after the same concept was defined in Schema.org.

BiblioGraph has been influenced by OCLC’s participation in the W3C Schema Bib Extend Community Group (Schema Bib Extend 2014d), which was convened in 2012 to help Schema.org meet at least the minimal needs of communities with a professional interest in bibliographic description. Among the active participants are authors of the Library Linked Data Incubator Group Final Report (Baker et al. 2011), data architects for individual libraries and library service providers, and members of publisher metadata community. Though they represent different constituencies, the members of the Schema Bib Extend Community Group pursue the common goal of monitoring Schema.org for conflicts and redundancies with the most common standards for bibliographic description and making formal recommendations for extensions. In addition, the Schema Bib Extend group lobbies for the use of Schema.org by libraries and works to accelerate its rate of adoption by publishing code samples, recipes, and tutorials (Schema Bib Extend 2014c; Scott 2014).

These successes are possible only through direct engagement with representatives from Schema.org, who ensure that the changes recommended by the library community fall within parameters that minimize the potential for disruption by other data producers. For example, Dan Brickley, who co-chairs the Schema.org task force for extension proposals with R.V. Guha (Guha and Brickley 2014), has specified that only ‘non-breaking’ changes can be accepted, such as new subclasses, new properties for existing classes, or properties that are promoted to a higher position in a class hierarchy to make them more broadly available. The Schema.org vocabulary also reflects some minor editing changes recommended by the user community. For example, deprecated property names such as CreativeWork-awards were changed from the plural to the singular form CreativeWork-award. BiblioGraph is also modified to remove clashes or redundancies as Schema.org evolves. For example, the bgn:VideoGame class was recently deprecated after the same concept was defined in Schema.org.

Schema.org managers are now formalizing a generic model for extension vocabularies. According to Guha (2015), Bibliograph.net represents a ‘reviewed extension,’ which is created with a set of contact points with Schema.org, i.e., the new subclasses and properties for existing Schema definitions we have already described. The extension is maintained by editors with backing from a particular community of practice, such as the Schema Bib Extend group. In the proposed new model, the BiblioGraph vocabulary would be uploaded to a Github repository owned by Schema.org, where it could be viewed from an interface accessible from http://bib.schema.org, which would integrate the extension vocabulary with the latest version of Schema.org, much as the Bibliograph.net site does now. Once the extension model is fully implemented, community groups would maintain only their vocabularies, and not the website that delivers it.

3.4.5 Other Models of Creative Works

OCLC’s model of creative works is only one outcome of the redoubled effort focused on bibliographic description undertaken by library standards experts after the publication of the Library Linked Data Incubators Group Report in 2011. Despite the current appearance of the markup, the OCLC model is a direct descendant of the British Library Data Model (Hodson et al. 2012; BL 2014), which predated the publication of Schema.org by several months and was the first large-scale demonstration of a linked data model of bibliographic description by a national library. The most impressive result was that nearly all of the textual fields in a reasonably complex MARC record were represented as URIs, except for irreducible string literals such as titles, summaries, dates, and assorted numerical values.

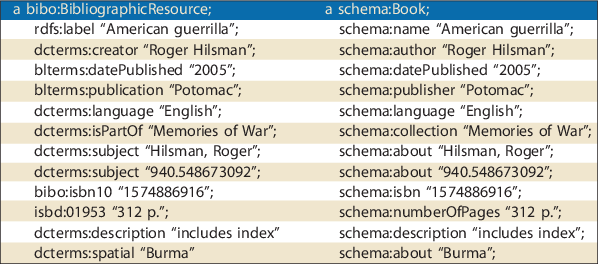

The British Library Data Model also contains references to many of the same entities recognized in the OCLC model of Works and has a similar configuration. But the British Library model is technically more complex and ontologically more opaque because it is assembled from terms defined in 14 namespaces. A description of American Guerrilla is an instructive example because the dataset that accompanies the British Library Data Model has complete RDF/XML and Turtle descriptions of this book and can be directly compared with a description available from WorldCat.org. Table 3.1 shows a simplified description in which the URIs are replaced with text strings corresponding to the name or label of the resource.

The descriptions excerpted in Table 3.1 are equivalent because nearly all of the classes and properties defined in the British Library Data Model can be expressed in Schema.org, primarily by one-to-one mappings or transparent lexical substitutions. Not only does this example support the argument that Schema.org is a reasonable starting point for a robust library resource description, but also that this solution is both a technical and a conceptual improvement. It is technically challenging to maintain URIs that make reference to a collection of namespaces, especially if they are defined in projects that primarily serve small, specialized academic communities, such as (de Melo 2014), whose long-term persistence cannot be guaranteed. Conceptually, it is difficult to interpret the true scope and intent of the British Library Data Model because the namespaces represent an ontological commitment to a large set of mature vocabularies and ontologies, which on close analysis might reveal untenable redundancies and semantic conflicts. Both of these problems are averted by adopting a single, more comprehensive standard—which, of course, did not exist when the British Library published their model and exists only partially now because Schema.org was not designed to serve the specialized needs of libraries.

OCLC’s model of creative works has also been influenced by other emerging linked data standards and protocols. For example, the distinction between Work-as-Content and Work-as-Product can be broadly mapped to the BIBFRAME Work-Instance division (Godby 2013), which has been hailed as an improvement over models derived from a literal interpretation of the FRBR Group I hierarchy, because it eliminates distinctions that have proven especially difficult to discover algorithmically. But OCLC’s model differs from BIBFRAME (LC 2014c) by placing a greater emphasis on modeling real-world objects for the purpose of discovery (Godby 2013; Godby and Denenberg 2015). The OCLC model of creative works has also been influenced by the draft W3C proposal for linking alternative representations of a document for discovery and fulfillment (Raman 2006). This protocol defines a generic information request that is fulfilled when the user specifies values for the language of the content, an edition identifier, and a file format appropriate for a particular rendering device. In our view, the abstract creative work corresponds to the generic information request, while the tangible versions of the creative work correspond to the document that is delivered. But the OCLC model differs from the Issue 53 protocol because it also accounts for the delivery of print materials and other physical objects.

3.4.6 The OCLC Model of Works: A Summary

The most important pragmatic argument for basing the OCLC model on Schema.org is summarized in Chapter 1: that this is the vocabulary understood by the world’s most important search engines. But another important reason is that Schema.org makes ontological sense. Since published books and other products of the human imagination are real-world objects, properties defined by third parties are understandable in the same way by members of the library community. Thus the Schema.org definitions of publisher, creator, ISBN, and nearly all of the other properties defined for Person, Organization, Place, and CreativeWork can be reused, eliminating the need to redefine these concepts in a specialized ontology that serves only the needs of libraries. Ever since Schema.org first appeared in 2011, we have believed that the vocabulary is incomplete rather than incorrect. But Schema.org is also growing rapidly. As we have shown, the addition of the GoodRelations ontology in 2013 has expanded the capacity of Schema.org to support enriched descriptions of library resources. The new accessibility features for CreativeWork and the recently announced taxonomy of Actions, which we have not yet had a chance to evaluate, may also be relevant to our goals. It is in the interest of the library standards community to monitor these developments because third parties may be doing much of the work that librarians had originally envisioned having to do themselves.

3.5 Discovering Creative Works Through Data Mining

In the rest of this chapter, we will briefly elaborate on a point that was first made in Chapter 1: that the RDF datasets being generated at OCLC is the result of a process that is far richer than the mapping of vocabulary from MARC to Schema.org and the newly defined terms available from extensions such as BiblioGraph.net. Instead, the goal is to build RDF datasets representing authoritative information about the six entities of interest in the current phase of our work—people, places, organizations, concepts, objects, and works—and define URIs that point to them. In this way, the knowledge locked in legacy metadata can be used to create next-generation library resource descriptions that are more machine-processable and project the expertise of librarianship outward to the broader Web. The evolving semantics of aggregations such as VIAF, described in Chapter 2, illustrate a path for moving forward with the development of authoritative resources for people, places, organizations, and concepts, since these entities fall within the scope of traditional library authority files.

Here we focus on Works—in particular, the distinctions defined in the FRBR Group I Model, and will describe the process of creating similar authoritative resources for these objects. The research described in Section 3.4 is the foundation for a workflow that discovers evidence in OCLC’s legacy data stores for the new subclasses of schema:CreativeWork, creates RDF descriptions of them, and assigns the appropriate URI and RDF type. The data mining procedure is more complex because it not only evaluates the structured data of library records but is also beginning look further afield to semi-structured and unstructured text, which we describe in Chapter 4. In addition, the workflow accepts the large and growing corpus of WorldCat as input and supplements it with information available in the linked data versions of the authority files discussed in Chapter 2, which are also being iteratively improved. Some of the results are fed back to the authority files, ensuring that the Works algorithms operate on cleaner input in the next iteration.

Given that these procedures were first devised to improve the organization and display of library catalogs, the algorithms for identifying Works and Manifestations are the most mature. But research currently underway has already produced successful methods for identifying Expressions and Items, which promise to increase the quality as well as the scope of library metadata.

3.5.1 Identifying Works and Expressions

The algorithm for discovering Works in a corpus of MARC records is described in Hickey, O’Neill, and Toves (2002) and Hickey and Toves (2009), and has undergone continuous refinement as WorldCat has grown. But the fundamental procedure has remained the same. In the first step, authors, contributors, and titles are extracted from the MARC main entry and controlled access fields, normalized to a key, and assigned to a cluster that was produced in an earlier iteration. If the author-title key matches exactly with a previously processed key, it is assigned to the same Work cluster. If not, a controlled extended match consults the name and title variants available from the corresponding Work description maintained in VIAF, including translated forms of the title–creating, in effect a ’super’-Work from which Expression-like relationships can be derived. In the current version of the algorithm, subsequent processes identify only ’translation’ relationships among the distinct creative works in this cluster, but other relationships are being studied. If all attempts at matching fail, a new Work cluster is created. In the second step of the algorithm, the Work clusters are mined to identify creators, secondary contributors, titles, description or summaries, and subjects. These processes are trivial if the Work cluster has only one record; and relatively straightforward if the cluster is large because the predominant values for these properties can be detected from simple frequency counts or counts weighted by library holdings. Work clusters are publishable only if they contain exactly one Work record from the previous iteration. Thus the algorithm is conservative and the residue requires human review.

As of April 2014, the Works clustering algorithm has been executed on about 80% of WorldCat without the need for extended matching. Among the millions of authors that can be extracted, fewer than 10,000 produce unstable results. But since these are the authors of the literary canon—William Shakespeare, Mark Twain, Anton Chekov, and others—whose names are controlled in authority files maintained by national libraries, this outcome can be translated into requirements for improving authority descriptions or aggregations such as VIAF. The run of the algorithm that generated the initial version of WorldCat Works dataset in April 2014 produced 194,928,712 clusters and 40,142,456, or 35%, contained more than one record. But these records are associated with nearly 75% of the holdings reported by the world’s libraries. Thus the small subset of WorldCat for which Work clusters are meaningful is also the most visible.

3.5.2 Identifying Manifestations and Items

When the FRBR Group I model was formulated in the 1990s, a MARC record accessible from an online catalog or an aggregate such as WorldCat was commonly interpreted as a Manifestation. The same interpretation is shared by metadata standards experts in the publishing community, who aligned Manifestation with Product, the top-level term in the ONIX specification, which was being developed at the same time as the FRBR model (Bell 2012). Since ONIX influenced the design of schema:CreativeWork, it is not surprising that Manifestations can be described in Schema.org with little need to define extensions.

In the linked data projects we have described in this book, a Manifestation is connected through the schema:workExample property to a Work, as shown in Figure 3.6 for Joy of Cooking. Yet an examination of the linked data shown in the inset reveals that the description is associated not with a Manifestation identifier, but with a WorldCat URL—in other words, a noisy surrogate for a Manifestation entity, which can be identified only by a clustering algorithm. If each bibliographic record contained only a single ISBN or other product identifier, no such computation would be necessary. But the publishing industry does not guarantee a one-to-one mapping between identical products and ISBNs because a single product may have more than one ISBN as the publisher supply chain moves from the assignment of ten-digit to thirteen-digit codes; conversely, multiple products may have the same ISBN as publishers address the issue of whether identical content delivered as a hardback book or an e-book requires separate identifiers (Dawson 2012).

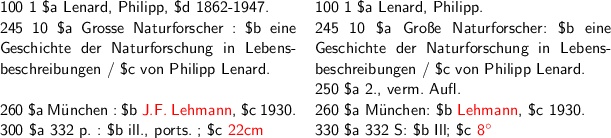

The other problem is that WorldCat is an aggregation of collaboratively contributed records, which means that it contains multiple descriptions of the same object or class of objects. Though duplicate detection algorithms can detect the most obvious redundancies, a deeper analysis is required to detect others, especially when the languages of description are different. This problem was defined by (Gatenby et al. 2012). An example from their analysis showing some of the details that must be reconciled is reproduced in Figure 3.13, which contains excerpts from a German-language and an English-language MARC record describing the same book, Grosse Naturforscher: Geschichte der Naturforschung in Lebensbescreibungen. A human reader can verify that these are descriptions of the same book because the title, author, publisher, and publication dates are the same, though the corresponding string values do not match exactly. The physical descriptions are also exactly the same, once an algorithm has been informed that ‘332 p.’ and ‘332 S.’ are equivalent because ‘Seite’ is the German word for ‘pages.’ The physical measurements are also the same because 8 inches equal 22 centimeters.

A process that collects such observations into a set of heuristics has been deployed on portions of WorldCat and only minor upgrades are required to assign Manifestation identifiers to the results. As the Gatenby, et al., study shows, these heuristics also improve the Work cluster algorithm because they consider a broader range of data, permitting the assignment of records to Work clusters that are missed when data associated only with authors, titles, and uniform titles is considered.

The only remaining FRBR category is the Item, about which we have little to report because the management of items is traditionally done by libraries, not aggregators such as OCLC. From a data processing perspective, it is obvious that Items present the same problems as Manifestations because aggregations such as WorldCat have multiple descriptions of the same thing, often in different languages. But before addressing this problem, we need to develop a taxonomy of what an Item can be and how various descriptions relate to it, which is the subject of a research project on aggregated descriptions of cultural heritage materials in discussed in Chapter 4. An added benefit is that the consideration of Items moves the discussion beyond the stewardship of published materials to archives, special collections, and digitized objects—resources that may someday comprise the largest segment of library collections. This focus might be expected to expose inadequacies in a model derived from an ontology designed to facilitate the movement of products in a marketplace, but we are optimistic that Schema.org is up to the task. Chapter 5 presents a sketch of a model for digital objects, an extension of the model described in this chapter. Once implemented, such a model could expose the availability of unique items held by libraries to the broader Web, perhaps through the model for library holdings that has already been developed.

3.6 Chapter Summary

This chapter completes the description, started in Chapter 2, of the semantic model that underlies the network of statements published as RDFa on bibliographic records accessible from WorldCat.org. Though it is an early draft, the process flow successfully creates machine-understandable statements about key entities— persons, organizations, places, topics, works, and objects— that populate the largest corpus of bibliographic descriptions managed by the library community. It is now possible to make subtle but sophisticated assertions about the domain of library resource management such as ‘A 1997 edition of Joy of Cooking, a book written by Irma von Starkloff Rombauer, is available for lending at the Grandview Public Library’ or ‘An edition of The Snow Queen, published in 1987 by North-South Books, is an English translation of the German translation Schneekönigin, which is translated from the Danish original Snedronnigen written by Hans-Christian Andersen.’

For the first time, such statements can be formulated in terms that are comprehensible to general-purpose search engines and other data consumers outside the library community. They are unambiguous and trustworthy because text strings such as ‘Hans Christian Andersen’ have been upgraded to resolvable references to real-world objects—or more idiomatically, ‘things’—and replaced with persistent, globally unique identifiers such as http://viaf.org/viaf/4925902, which point to machine-understandable hubs of authoritative information managed by the library community and affiliated professionals.

Chapter 2 argues that library authority files are realistic predecessors to the authoritative hubs seemingly required by the conventions that make up the linked data paradigm. Authoritative hubs for creative works defined with the different levels of concreteness or specificity in the FRBR Group I hierarchy are also required for addressing the most important use case for linked data in the domain of libraries and librarianship: facilitating the discovery and delivery of the resources that satisfy the information needs of the public. But hubs for creative works have no direct antecedent in legacy standards or data stores and must be generated from algorithms operating on bibliographic descriptions.

The first result is WorldCat Works, which contains globally persistent URIs for nearly 200 million Works that resolve to descriptions modeled in Schema.org. They are automatically derived from WorldCat catalog records using algorithms developed by OCLC researchers working on the empirical discovery of the FRBR conceptual model in collections of bibliographic descriptions maintained by libraries. Though WorldCat Works is still experimental, its significance is already being recognized. For example, linked data experts at the Library of Congress have acknowledged that WorldCat Works are compatible with BIBFRAME Works and plan to include WorldCat Work URIs in future BIBFRAME descriptions (Godby and Denenberg 2015). Researchers participating in the ‘Linked Data for Libraries’ (or LD4L) project, expect to do the same. LD4L is a joint project led by libraries at Cornell, Harvard, and Stanford Universites and funded by the Institute for Library and Museum Studies, or IMLS (2015). The anticipated outcome is a set of cross-references among items in the collections held at the three participating institutions where none existed before (LD4L 2015a). When the results of these experiments become available, WorldCat Works can be evaluated as a collection point for links in the Semantic Web, a concept we introduced in Chapter 1. If the promise of linked data is upheld, the outcome should be greater visibility for libraries and their contents on the Web. Increased clickthrough rates to libraries that correlate with the inclusion of Work URIs in the RDF statements published on WorldCat.org have already been reported (Fons 2015).

Nevertheless, the results described in this chapter are a baseline and a proof of concept, a demonstration of a draft model and a set of machine-understandable statements that can be discovered in over 300 million legacy bibliographic records. But the model, as well as the processes that discover evidence for it in legacy data, are positioned for rapid maturation. Chapter 4 describes algorithms that consider a broader range of evidence for the entities and relationships that populate the resources managed by libraries. So far, the development of models has focused on monographs, but projects are already underway that expand their scope to include digital objects, the contents of institutional repositories, and electronic journal articles. Some of these projects are mentioned in Chapter 5. In addition, our collaboration with the Library of Congress is enhancing the interoperability of OCLC’s linked data models with BIBFRAME. This work aims to strike a balance between description and discovery, which recognizes the professional cataloger’s requirement for scholarly detail and precision, while making the case that much of the domain of library resource description is comprehensible to the information-seeking public and useful in the broader Web.

Linked data representations of creative works representing the perspective of librarianship have come a long way in just three and a half years, when the authors of the W3C-sponsored Library Linked Data Incubator Group Final Report could document only modest progress on this difficult problem. A plausible direction is now clear, and many of the issues that must still be addressed are well understood.