REALM Project

REopening

Archives, Libraries,

and Museums

Resources

Resources > Creating a museum exhibit during a global pandemic

COVID-19 and curation: Creating a museum exhibit during a global pandemic

Amy McKune has spent the first half of her career (so far) in a curatorial role and the second half in collections management. Since 2017, she has blended her two passions as curator of collections at The National Museum of Toys and Miniatures in Kansas City, MO. She manages the collections department and shares exhibit development and interpretive duties with the curator of interpretation. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Amy was in the middle of developing a new temporary exhibit. The pandemic changed how the collection was managed, how the exhibit was developed, and how the museum interacted with its peers across the country that were lending objects for the project. We talked to Amy about how the pandemic changed that exhibit process and how she thinks it will change exhibits in the future.

Amy McKune has spent the first half of her career (so far) in a curatorial role and the second half in collections management. Since 2017, she has blended her two passions as curator of collections at The National Museum of Toys and Miniatures in Kansas City, MO. She manages the collections department and shares exhibit development and interpretive duties with the curator of interpretation. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Amy was in the middle of developing a new temporary exhibit. The pandemic changed how the collection was managed, how the exhibit was developed, and how the museum interacted with its peers across the country that were lending objects for the project. We talked to Amy about how the pandemic changed that exhibit process and how she thinks it will change exhibits in the future.

The interview below has been edited for length and clarity.

How did your team transition to working remotely? How do you manage a collection from home?

Luckily, we had just transitioned to an online collections management system right before the pandemic. When the pandemic hit, our registrar was able to work from home to do a lot of data clean-up that needed to be done after the migration. That kind of work can get pushed aside when you are in the building and being home let her focus on that.

Of course, we couldn’t walk out of the building and not monitor the collection, but early on there wasn’t a lot of communication in the field about what people were doing to manage their collections remotely. Before we walked out the door, we arranged for our collections manager to regularly visit the museum and our off-site storage to make sure that the collection was okay. As the pandemic and need for remote work extended, we learned from several larger museums that the staff either were not allowed in the building at all or had to seek permission in advance to enter, so we felt very lucky to have the flexibility to do what needed to be done to effectively monitor our collection.

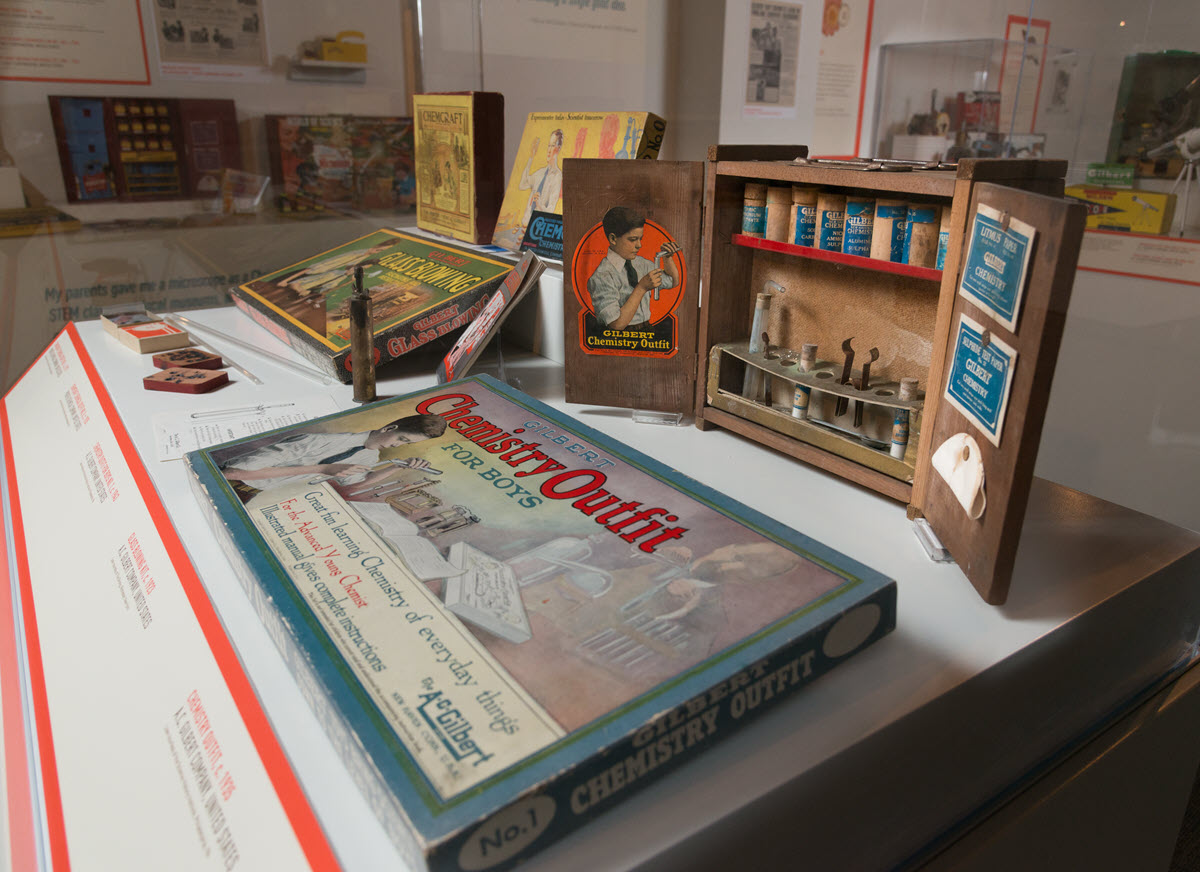

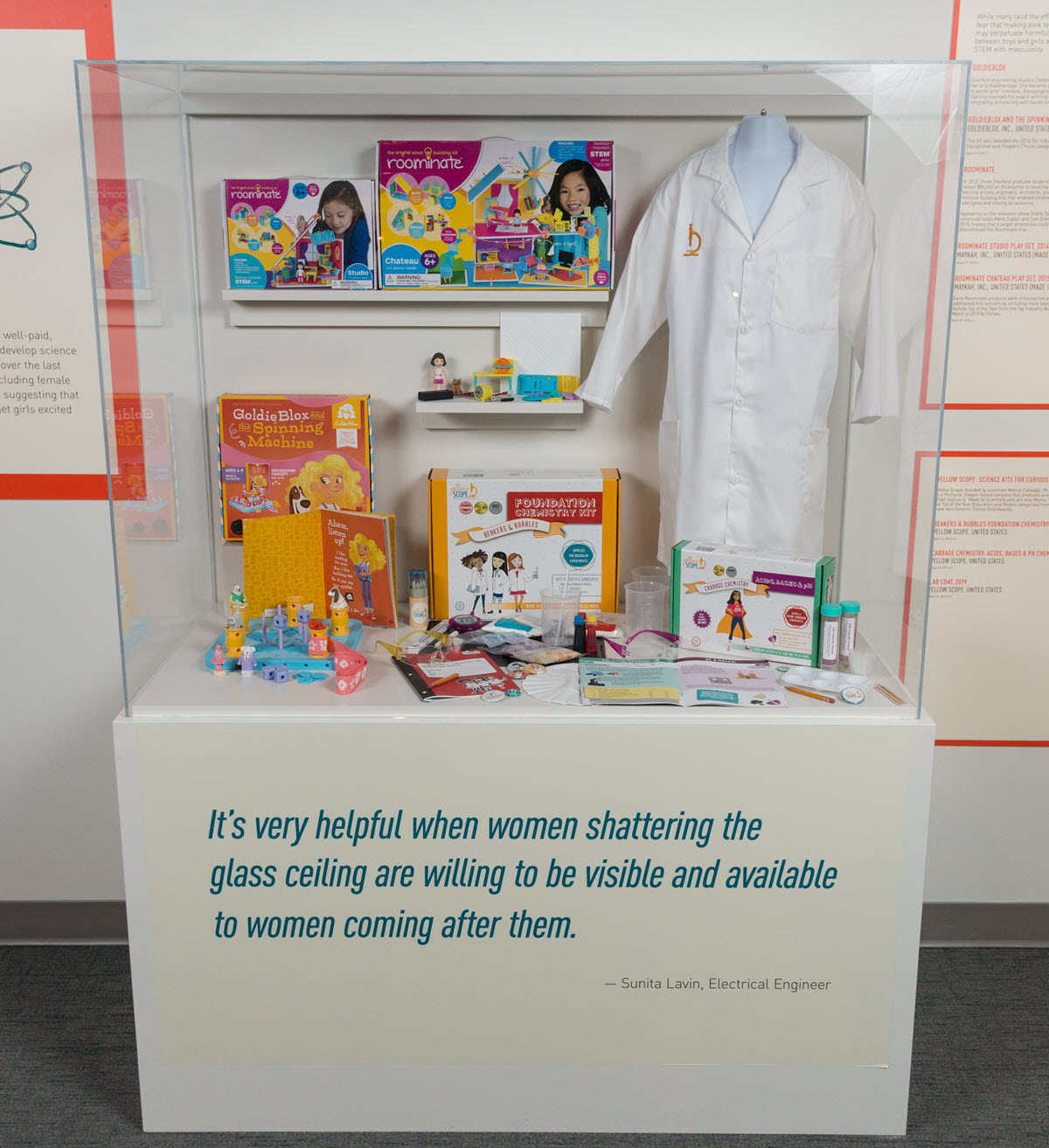

When we switched to remote work, I was in the middle of curating an exhibit called Bridging the Gender Divide: Toys that Build STEM Skills, so it was very easy for me to do that work from home and have the quiet time I needed. The one problem we had was that the exhibit was supposed to open in May, and of course we weren’t even in the building in May. We were out of our building from mid-March to mid-July, so we ended up pushing back the opening to July 15. Bridging the Gender Divide was about the toys that children play with that help them develop skills that are instrumental in STEM careers, like spatial and math skills, and how the marketing for those toys was very gender-biased for more than a century. To cover that, we needed to borrow quite a few objects. We had four different lending institutions, two close to home (the Linda Hall Library and the Kansas Historical Society) and two far afield (the Strong Museum of Play and the Science History Institute). For the lenders closer to home, we could just drive there, but for those in other states, the pandemic made the logistics of loaning objects very challenging. So, we pushed the date back so we could get those very important loans from our lending institutions, and we also decided to extend the exhibit until September 5, so it lasted14 months instead of nine.

Of course, with an extended exhibit duration, there was concern about increased artificial and natural light exposure, since a lot of these objects are very sensitive to light. However, the lights were off while we were closed, and even when we reopened, we didn’t reopen immediately to our usual six days a week. Based on those factors, we were able to calculate how much light exposure there would be, and then the lending institutions were comfortable extending their loan period.

When we started booking transit for the loans we would receive for Bridging the Gender Divide, we discovered that the fine art shipping company had furloughed some of its staff and they had just returned to work. So even if we had been able to be in our building and the lending institutions could be in their buildings, we still wouldn’t have been able to get the objects here any sooner because we wouldn’t have been able to ship them. Luckily everyone came back around the same time frame and could prepare the objects for loan and get them shipped.

The collections manager and I were the first staff to return to the building so that we could start installing Bridging the Gender Divide. There were lots of times that it was just the two of us working in the building, and we were able to maintain distance and wear masks when working in close proximity. It was interesting to me how much our job responsibilities really shaped how we could respond to the pandemic. When I was working on exhibit development, I could do that remotely, but the collections side of my job meant I needed to be more physically present and have access to materials.

How did the pandemic change the museum’s approach to exhibits?

We’ve put a lot of emphasis over the last several years on interactives in exhibits, so not knowing if the virus could be spread by surface contact was a problem. I was tasked with looking at the three interactives that I had planned for the exhibit and figuring out if it made sense to have all three, how we would need to change them, or if we’d need to eliminate some.

In Bridging the Gender Divide, we had a matching game featuring 12 women who made major contributions to STEM during their lifetimes, with the earliest being Ada Lovelace, considered to be the first computer programmer. I was going to do this matching game, but because of COVID, we turned it into a coloring book. The visitors could handle their own personal copy, take it into the exhibit to do the matching game, and then take it home to color it. Luckily our manager of visitor services could do sketches based on photographs of the 12 women and we were able to use her art for the coloring book. That was a really good solution that worked well for us—in fact, continuing the exhibit experience at home was a huge bonus.

We also built a model train set-up that demonstrated the STEM skills you would need to put together a model train. That was going to be something that the visitor would activate with a button, but we turned it into a motion sensor. With the exhibit open longer than planned, the train required more and more attention from our collections manager as the 14 months went by. Toward the end, she had to clean the track about every two weeks to keep the train running. The only problem with the motion sensor was when there was a family with a group of children. We had the train running for a minute, but a minute is a long time if you are waiting for your turn to make the train start. So that and keeping it running for the duration of the exhibit were the main challenges.

The last interactive wasn’t as easy to solve. Hammerspace Community Workshop, a local makerspace, was doing a class on building a bar top arcade game, and we purchased the kits from them to build three of these consoles. A programmer from Hammerspace did the programming for us, and I found open-source games that teach STEM skills. In the opening screen, we talked about the skills that would be developed by each game. We had everything lined up for this great interactive—but an arcade game has to be hands-on. How could guests still use their hands for this? We ended up purchasing freestanding disinfecting wipe dispensers with built-in trash cans, so visitors could clean the game themselves and throw the wipes away right there.

We used the wipe dispensers in another location in the museum where we had an interactive that we really didn’t want to close—by providing visitors with the chance to clean for themselves, we felt people could continue to use it. As it became more apparent that surface transmission wasn’t as big of an issue, we started gradually reopening our interactives. It really depended a lot on the interactive. For example, we have microscopes that show miniatures that are really hard to see without a microscope. We still have our microscopes closed because we still don’t think it’s best for visitors to use them.

What changes in practice do you think will continue?

Transitioning a lot of our programming to online was immensely beneficial. It took a huge amount of effort, but I think we’ll continue a lot of those initiatives because we can reach a much larger audience. We get almost 40,000 visitors a year—that’s a good number for a small museum, but that’s still only 40,000 people we can reach in a year. If we put something online, we can reach a much larger number. That’s probably the best thing that came out of it. With our latest exhibit, we invested in having a professional photographer come out and document the exhibit so we could create a digital tour that would live on after the exhibit closed. So, we are continuing to think about how content can persist digitally.

For good or bad, I think that interactives will be very seriously scrutinized from here on out by everybody in the museum field. Before the pandemic, we had people telling us we didn’t have enough interactives, and then all of a sudden people didn’t really want to do interactives or we didn’t want to have them available because we weren’t sure if they were going to cause a problem. I think we’ll give a lot more consideration to what each interactive will accomplish and whether this is the best way to do it. I think most museums, except science centers, are going to do fewer interactives because of a new set of implications and concerns. On the other hand, if you don’t have them, it’s harder to have people engage. I expect we’ll look to have these experiences being interactive in different ways, like the motion sensor instead of pressing a button. We’ll be challenged to find ways to make things interactive without being as physical, and I’ll be really interested to see how the approach to this work changes in the field.

Photos courtesy, Amy McKune